High-protein diets are all the rage these days, with people swearing by them for weight loss, muscle building, and overall health. But did you know that eating too much protein might actually shake things up in your gut? Scientists are finding that excessive protein intake can alter your gut microbiome, which could have some surprising effects on digestion and well-being. Let’s dive into how this happens and what you can do to keep your gut happy.

What Happens to Your Gut Bacteria When You Eat More Protein?

Your gut is home to trillions of bacteria that help digest food, support immunity, and even affect your mood. When you load up on protein, your gut bacteria shift to accommodate the change. This often means more protein-fermenting bacteria and fewer fiber-loving microbes (Beaumont et al., 2017). While this might sound fine, it can lead to the production of potentially harmful byproducts like ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, and branched-chain fatty acids (BCFAs) (Davila et al., 2013).

The Downside: Unwanted Byproducts

When your body digests protein, it undergoes fermentation—especially in your colon. This process releases metabolites that might not be great for your gut health. Studies suggest that excessive protein fermentation can increase levels of ammonia and hydrogen sulfide, both of which are linked to inflammation and even a higher risk of colorectal cancer (Windey et al., 2012).

If your protein intake comes mostly from red and processed meats, there’s more reason to be cautious. Research has linked these foods to an overgrowth of bile-tolerant bacteria, which may contribute to inflammation-related diseases (Zhu et al., 2020).

The Good Bacteria May Take a Hit

While protein fuels muscle growth and metabolism, overloading on it—especially at the expense of fiber—can lower the number of beneficial bacteria like Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli (O’Keefe et al., 2015). These friendly microbes help keep your gut lining strong and inflammation in check by producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). Unfortunately, when fiber intake is too low, SCFA production drops, and your gut health can suffer (Conlon & Bird, 2015).

Finding the Right Balance: Why Fiber Matters

The best way to protect your gut while following a high-protein diet? Eat enough fiber! Fruits, veggies, and whole grains provide prebiotics that fuel beneficial gut bacteria and boost SCFA production (Singh et al., 2017).

You can also diversify your protein sources by including plant-based options like beans, nuts, and tofu. These foods contribute to a more diverse microbiome and help prevent gut imbalances (Marette et al., 2021).

A high-protein diet can have both positive and negative effects on your gut. While protein is essential for muscle function and overall health, too much—especially from animal-based sources—can throw your gut bacteria out of whack. The key is balance: include fiber-rich foods and plant-based proteins to support a healthy gut and long-term well-being.

References

- Beaumont, M., et al. (2017). "The gut microbiota metabolizes dietary proteins into host-signaling metabolites." Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 14(9), 531-545.

- Conlon, M. A., & Bird, A. R. (2015). "The impact of diet and lifestyle on gut microbiota and human health." Nutrients, 7(1), 17-44.

- Davila, A. M., et al. (2013). "Intestinal luminal nitrogen metabolism: Role of the gut microbiota and consequences for the host." Pharmacological Research, 68(1), 95-107.

- Marette, A., et al. (2021). "The interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and health." Annual Review of Nutrition, 41, 371-393.

- O’Keefe, S. J., et al. (2015). "Fat, fibre and cancer risk in African Americans and rural Africans." Nature Communications, 6, 6342.

- Singh, R. K., et al. (2017). "Influence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human health." Journal of Translational Medicine, 15(1), 73.

- Windey, K., et al. (2012). "Intestinal bacterial metabolism of protein: Dietary and functional consequences." Gut, 61(4), 569-579.

- Zhu, Y., et al. (2020). "Red meat and processed meat consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies." European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 74(1), 8-15.

Karla Mingo believes that her greatest gift as a cancer survivor is the ability to live with gratitude and thankfulness.

Karla Mingo believes that her greatest gift as a cancer survivor is the ability to live with gratitude and thankfulness.

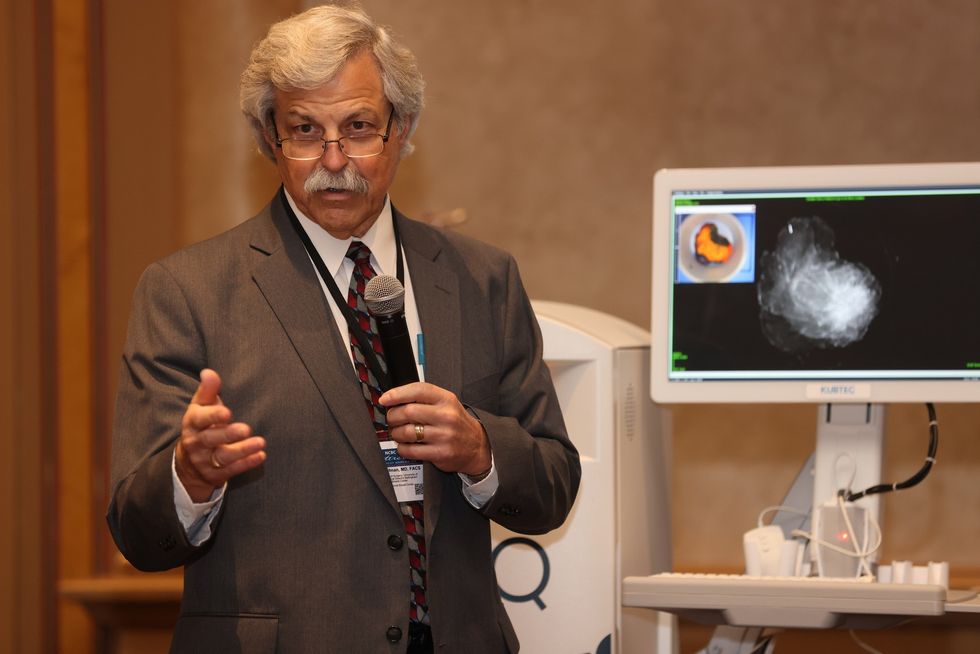

Dr. Cary S. Kaufman teaches the "Essentials of Oncoplastic Surgery" course through the National Consortium of Breast Centers, providing breast surgeons around the world with advanced techniques for optimal breast surgery outcomes.

Dr. Cary S. Kaufman teaches the "Essentials of Oncoplastic Surgery" course through the National Consortium of Breast Centers, providing breast surgeons around the world with advanced techniques for optimal breast surgery outcomes.